Venice 2025: The Verdict

.

VERDICT: Despite dissent over the jury's Golden Lion pick, Venice was at its peak in many ways this year.

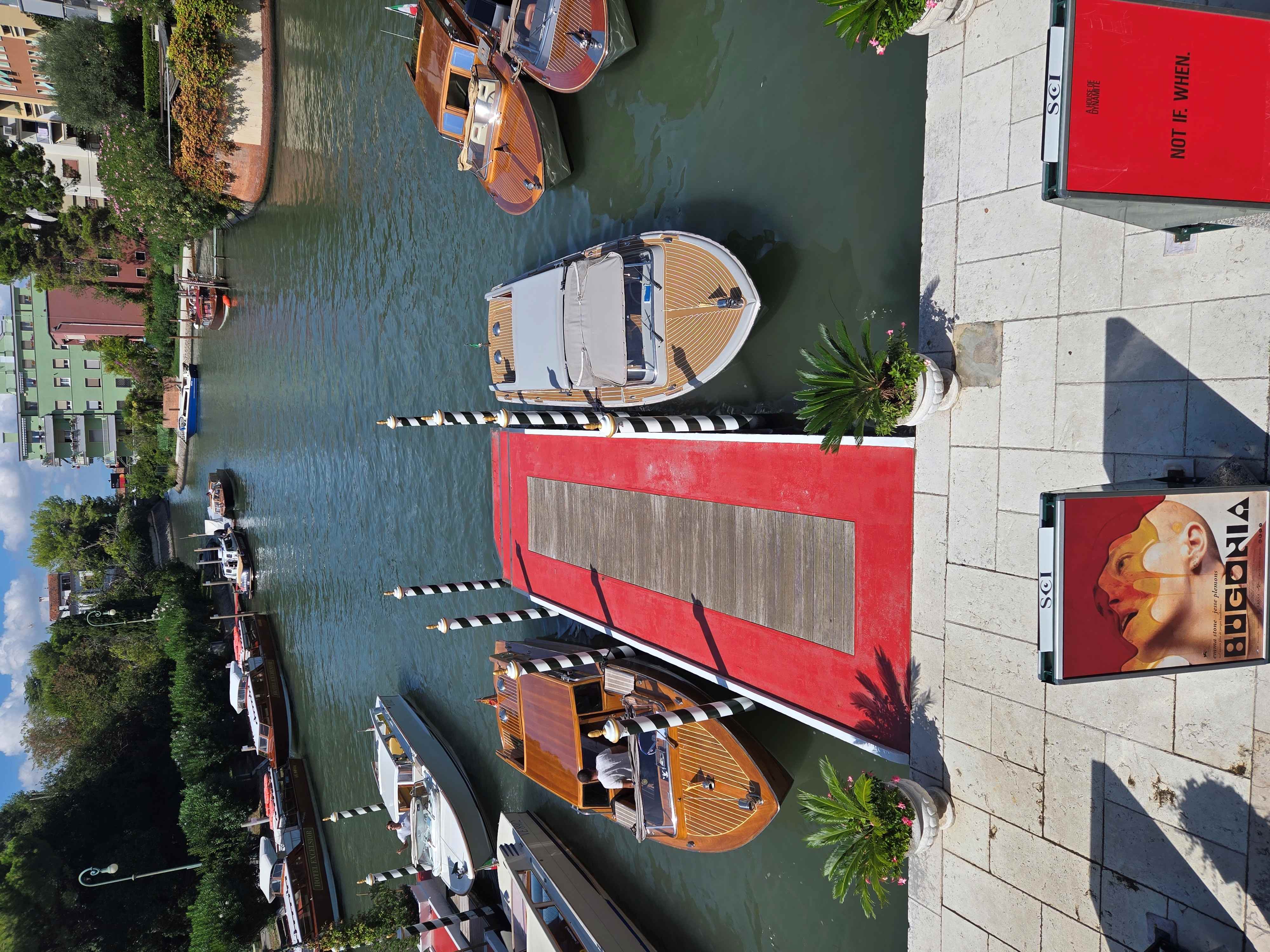

It had been one of the best Venice film festivals in memory. The weather was balmy Indian summer, apart from a few days punctuated by drenching showers. As soon as the films began unspooling with Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia, the opening film, it was clear that festival director Alberto Barbera and his programmers had a winning selection. Festival goers flocked to the Lido, and this year the Vivaticket booking system worked efficiently. It allowed press and industry to get into theaters by simply scanning their badge, simplifying life and speeding up everything.

In brief, an enviable year to be attending the festival. Then the awards were announced.

Most would agree with the principle that films are not supposed to be propaganda vehicles dictated by political agendas. But the extreme tension the world is living through has everyone on red alert and girding for regime change and war. Many of the Venice selections reflected the urgency of the moment.

In competition, there was Kathryn Bigelow’s edge-of-seater A House of Dynamite, a disaster thriller about the rising probability of a nuclear war breaking out; and there was Olivier Assayas’s The Wizard of the Kremlin recounting Vladimir Putin’s rise to power from an insider’s perspective. Pietro Marcello’s Duse, featuring a star turn by Valeria Bruni Tedeschi as the great Italian actress, set the whole story against the background of the rise of Fascism and how it affected her life… Well, none of these films won a prize.

But the sheer immediacy and emotion of The Voice of Hind Rajab grabbed audiences by the throat thanks to Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania’s intensely moving reenactment of the Israeli army’s shooting of a 5-year-old Palestinian girl trapped in a car in Gaza, after all efforts of a Red Crescent rescue team proved futile. It captured the hearts of critics and the public alike. And it was generally considered the front-runner for the Golden Lion.

So there was widespread disbelief and even anger among critics (and even many in the awards night audience) when Alexander Payne’s jury handed the festival’s top prize to Jim Jarmusch for Father Mother Sister Brother. Boasting a starry ensemble cast including Adam Driver, Cate Blanchett, Tom Waits and Charlotte Rampling, the veteran U.S. indie director’s whimsical triptych of droll family vignettes is a slight, low-key charmer. But compared to Ben Hania’s much more powerful and emotionally wrenching The Voice of Hind Rajab, this pick for the Golden Lion felt strangely timid and wrong-headed. Great cinema is not obliged to wrestle with prickly real-life issues, of course, but in this context rewarding such an apolitical film as Jarmusch’s felt extremely political. The Voice of Hind Rajab received instead the Silver Lion, the festival’s Grand Jury Prize.

Two other women directors brought impressive, stunningly original, career-high films to competition. Ildiko Enyedi won the Fipresci Prize with Silent Friend, three thematically connected stories set in different time periods at a German university, whose protagonists have a burning desire to communicate with plants. The central character is an ancient and presumably lonely female Gingko biloba tree, and by the end of the film it is hard to doubt this magnificent plant thinks and feels.

One of the most thrillingly original competition premieres was Mona Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee, an audacious avant-garde musical biopic of the messianic British woman who founded the Shakers religious sect in the 18th century. Placing Amanda Seyfried at the whirling centre of an all-singing, all-dancing ensemble cast, Fastvold’s delirious period pageant almost felt like a thematic sister film to her husband and creative partner Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist (2024), another epic study in monomania which made a big splash at Venice last year. Critics were divided, but this is bold, risky, female-driven auteur film-making.

The most prestigious literary adaptation in Venice was Francois Ozon’s achingly cool monochrome take on the classic Albert Camus existentialist novel L’Etranger, which premiered in the main competition. Starring sulky beauty Benjamin Voison as the emotionally numb anti-hero Mersault, who sleepwalks into a random murder, then refuses to save his own life with performative fake remorse, Ozon’s stylish mid-century modernist treatment is meticulously faithful to the text without being reverential. It may well provide the veteran French auteur with a rare international hit.

More unconventional literary works were scattered across the festival program, including two very different films riffing on Dante’s Divine Comedy. The first, simply called Divine Comedy, was a slight but charmingly droll farce about the absurdities of censorship in Iranian cinema from much-banned film-maker Ali Asgari. Meanwhile, Julian Schnabel’s In The Hand of Dante adapted the 2002 Nick Tosches novel about mobsters chasing Dante’s priceless original manuscript into a sprawling, bloated, testosterone-drunk, all-star train-wreck. Think Coppola’s Megalopolis with a plot by Dan Brown. But, amazingly, even less fun than that sounds.

Among the low-key gems tucked away on the Venice fringes was Critics Week closer 100 Nights of Hero. British first-time feature director Julia Jackman makes a charmingly quirky version of Isabel Greenberg’s post-modern graphic novel, a queer feminist fairy tale co-starring Emma Corrin and Maika Monroe. In the Orizzonti section, Thai film-maker Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit depicted a young couple living lives of quiet desperation under late capitalism in his hauntingly bleak workplace drama Human Resource. Meanwhile, the stand-out discovery of Venice Days was 24-year-old Swiss-Kenyan director Damian Hauser’s Memory of Princess Mumbi, a hugely inventive mash-up of tragic love story, meta-fictional docu-thriller and eye-popping AI fantasia. All are fresh talents with bright futures.

An extraordinary second film in Venezia Spotlight was Shahad Ameen’s Hijra, the fast-moving story of a pious elderly women and her two teen granddaughters who are traveling to Mecca to make the pilgrimage of a lifetime when one of the girls suddenly disappears. Narratively and philosophically complex, it opens a respectful but fascinating exploration of Islam.

Two top Latin American directors, Mariana Rondón and Marité Ugás, worked together on another Venezia Spotlight standout, It Would Be Night in Caracas. A woman of almost 40 finds herself all alone in a hostile city when her mother dies. Portraying the violence of the streets, police, gangs and squatters, the film builds a picture of Venezuela as a country of constant tension, fear and danger. Winning the Orizzonti Award for Best Film was an unforgettable drama from Mexico, En el camino (On the Road) by David Pablos, casting a frank glance at Mexican long-haul truck drivers who relax with drink, drugs and promiscuous sex. In a sordid world imbued with violence and cruelty, a married trucker falls for a 20-year-old boy on the run from the cartel.

Italian genre cinema made a good showing for itself in no less than two midnight screenings, a slot that used to be a fixture in the Marco Müller era and has become a more sporadic occurrence under Alberto Barbera. Most of the headlines focused on Paolo Strippoli’s The Holy Boy, owing to the bigger promotional effort behind it and the director’s track record in Italy, but even more impressive was Virgilio Villoresi’s Orfeo, an independently produced adaptation of the Orpheus myth where mood, performance, animation and passion come together to deliver a journey to the underworld that is brief (74 minutes) but fascinatingly dense.

Circling around to the organizational front, the festival proved, once again, ill-equipped to deal with torrential rain, a feature on the Lido landscape year after year. In 2010, the weather led to the press room to being shut down for most of the day, as the water was leaking onto the floor of the Palazzo del Casinò. This year, a sudden downpour paired with a Q&A running long delayed the start of the press screening for Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt, as staff didn’t have the heart to send the people still inside the Sala Darsena to brave the elements. Unfortunately, news of this had failed to reach the journalists waiting outside, some of whom eventually bailed on the screening to avoid the combined effects of air conditioning and soaking wet clothes and shoes. Communication and scheduling could certainly benefit from an upgrade in future editions. And what about putting up some temporary canvas cover during the festival?