Jihan K was only six years old when her father Mansur vanished from his Cairo hotel room, never to be seen alive again. In My Father and Qaddafi, the young Arab-American director weaves a cinematic patchwork of fragmentary memories, archive home video clips, fading photos, nostalgic music and contemporary interviews. The resulting film is part tender memorial, part murder mystery, and part family therapy session. Around this deeply personal story, Jihan adds a broader sociopolitical framework sketching out the last tragic century of Libyan history, from genocidal colonial occupation to ongoing postcolonial struggles, from tyranny to anarchy.

The thirty-something Jihan is a first-time director, and her scrambled narrative feels a little messy in places. But this deeply personal passion project is briskly told and never less than compelling, with an emotional bite and an arty collage style that elevates it above dry history lesson. Accessible to anyone with a casual interest in world affairs and Middle Eastern politics, My Father and Qaddafi should enjoy plenty of festival play following its Venice world premiere this week, with healthy potential for art-house interest on small or big screen.

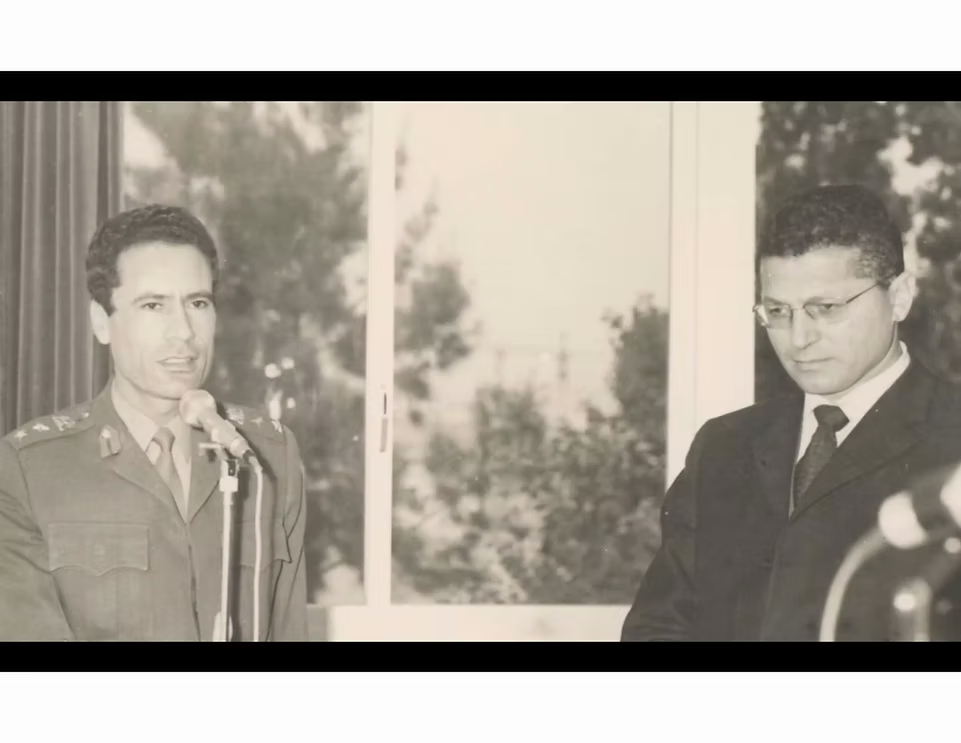

The film’s elusive star is Jihan’s father Mansur Rashid Kikhia, a former diplomat and human rights lawyer who served under Libyan’s long-serving murderous dictator Muammar Qaddafi as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ambassador to the United Nations, and other high-ranking posts. A well-travelled polyglot and idealistic champion of Pan Arabism, Kikhia was a natural mediator who favoured compromise and dialogue over factionalism, but he later split from the regime in protest at Qaddafi’s brutal executions of opponents. In 1980, he settled in the US, where he met and married Jihan’s mother, Syrian-American artist and activist Baha Al Omary.

Despite living in exile, Kikhia continued to push for political change in Libya, forging strong connections with its divided opposition movement. He was even being tipped as a possible replacement leader if Qaddafi was deposed, which probably sealed his fate. In December 1993, he was abducted by persons unknown in Cairo following a meeting of the Arab Organization for Human Rights. Suspicion naturally fell on Qaddafi, backed up by a CIA report which laid the blame on Egyptian agents working in tandem with Libyan security forces. But the regime denied any involvement, brushing off high-profile news coverage, and interventions by his family, who sent heart-breaking video messages to Qaddafi seeking some kind of clarity. Jihan’s mother even met with the Libyan leader in 1995, a tragicomic exchange of cynical evasions that she recalls here. A lively and outspoken interviewee, Baha is an asset to the film.

In a macabre twist, Kikhia’s body was finally discovered 19 years after he disappeared, inside a freezer in a regime-linked villa in Libya in late 2012, part of the flood of grim revelations that followed the Arab Spring uprisings and the violent death of Qaddafi at the hands of an angry militia. In a brief respite between civil unrest, Kikhia was given an official state funeral in his home city of Benghazi, attended by Jihan and family. More than a decade later, questions remain about how and when he died, and who exactly was behind his abduction. Even so, the director glumly concedes that she has been given a degree of closure denied to thousands of other Libyans, whose loved ones simply vanished forever.

Densely layered with music and lyrical imagery, My Father and Qaddafi is both factual documentary and audiovisual poem, a moving personal journey with wider resonances. Anxious to maintain a connection to her own ancestral Libyan identity, Jihan is mourning not just her lost father but also her lost fatherland, seeking to preserve memories of both in a period of mass forgetting. “I don’t want my father to disappear a second time,” she says in her Venice press notes. To that end, she also interviews relatives, friends and former colleagues of Kikhia on camera, who despair about the current catastrophic state of Libya. “Back then we had just one dictator,” one says, “now we have a thousand dictators.”

Director, screenwriter: Jihan K

Cinematography: Micah Walker, Mike McLaughlin

Editing: Alessandro Dordoni, Chloë Lambourne, Nicole Hálová

Music: Aleksander Pankowski Vel Jankowski, Barna Zsolt Szoke, Bisan Toron, Dominik Svoboda, Didier Monge, Fryderyk Lutynski, Grzegorz Lapinski, Kristjan Ruus, Magda Szczebiot, Magdalena Sowul, Michal Ostrowski, Salka Valsdóttir, Simone Giuliani, Tiago Correia-Paulo, Zuzanna Ossowska

Producers: Jihan K, Andreas Rocksén, William Johansson Kalén, Dave Guenette, Mohamed Soueid, Sol Guy

Production: Desert Power (US), Laika Film & Television AB (Sweden)

World sales: MAD World, Cairo

Venue: Venice Film Festival (out of competition)

In English, Arabic, French

88 minutes