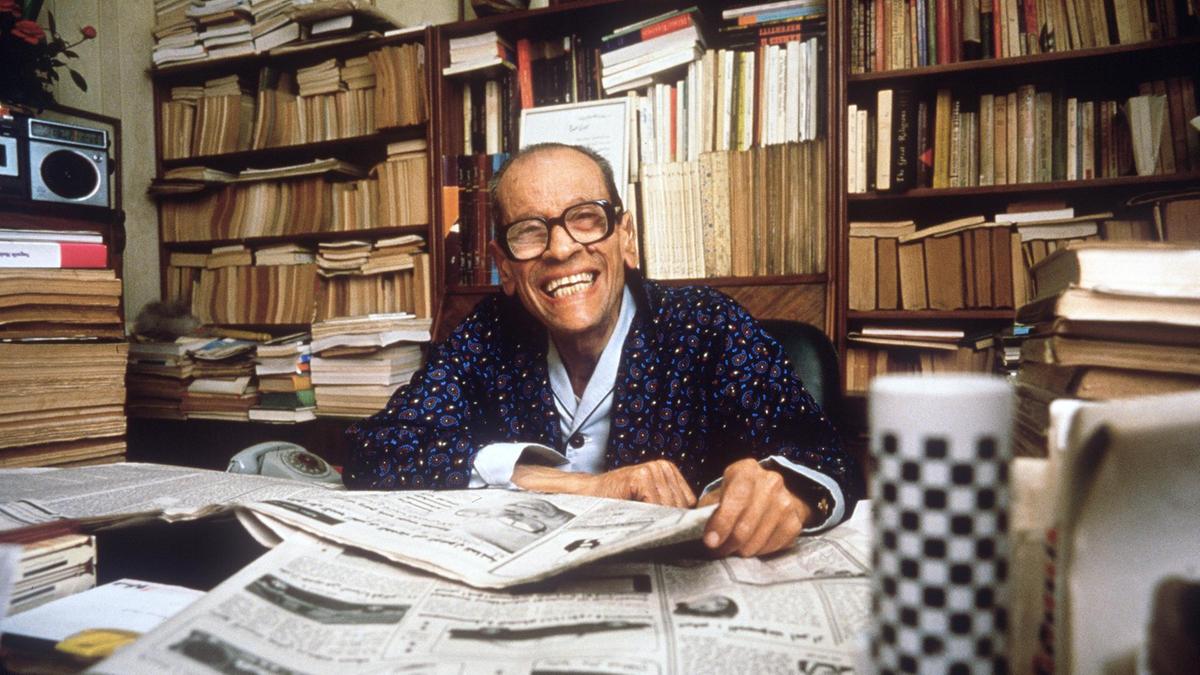

Naguib Mahfouz Still Walks Cairo’s Film Scene

.

VERDICT: Almost 20 years after his death, the legacy of writer Naguib Mahfouz continues to be present on the Egyptian cultural scene.

Talaat Harb Street, downtown Cairo. Passing by Café Riche, one can still see young people, literature students, and tourists taking pictures in front of it. Among its most famous patrons was legendary novelist and screenwriter Naguib Mahfouz, the first Arabic author to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988. Mahfouz’s enduring legacy is engraved in the Egyptian mindset, whether it is on carryalls with his picture, portraits on the walls of the Ministry of Culture, his statue close to the Egyptian Opera House. But let us consider his extensive influence on Egyptian cinema, arguably the country’s most important pillar of popular culture.

Starting in the 1940s, he worked as a screenwriter shaping what is now known as Egypt’s realist cinema, contributing to its most enduring screenplays. As a novelist, his stories, dialogue, and plots provided filmmakers with a bottomless archive of material, narrating stories rooted in Cairo’s streets and alleys, exploring moral ambiguity and conflicts that go beyond the usual poles of tradition and modernity. Around 28 films were adapted from Mahfouz’s novels, the majority translating his themes of social inequality, psychological fragmentation, and spiritual crisis into cinematic language.

This year the Cairo Film Festival is screening seven restored films written or adapted by Mahfouz in an extensive programme that features 22 Egyptian classic films. The restored classics that showcase Mahfouz’s work include Cairo 30 (1966), adapted from his novel Cairo Modern; Khan al-Khalili; Palace Walk, adapted from Bayn al-Qasrayn (the first volume of The Cairo Trilogy); Palace of Desire, adapted from Qasr al-Shawq (the second volume of the trilogy); The Beggar, adapted from Al-Shahhadh; The Mirage, adapted from Al-Sarab; The Quail and Autumn, adapted from Al-Summan wal-Khareef; and The Road, adapted from Al-Tariq.

In addition to the classics, his cinematic influence is present in this year’s Short Film Programme. Egyptian director Abdel Wahab Shawky is premiering his short The Last Miracle, which was supposed to open last year’s El Gouna Film Festival but was censored by Egyptian authorities, with no explanation, at the last minute. It will see its world premiere in Cairo, where the film’s stort unfolds.

Still from The Last Miracle

The inspiration for the film comes from Mahfouz’s short story The Miracle from the collection The Black Cat Tavern. The screenplay is written by Mark Lotfy and Abdelwahab Shawky and is Shawky’s debut short. The story follows Yehia, who came to Cairo to become a poet but instead became a journalist. Played brilliantly by Khaled Kamel, the character sits inside a dimly lit bar and receives a call from a man claiming to be a holy person, informing him that he is “the chosen one.” Depressed and full of despair, Yehia quickly believes this message and convinces himself of its truth.

In the film, Shawky questions this fragile belief but allows viewers to see the temptation one might feel when told they are a person of “miracles” to abandon the mundane job of writing newspaper obituaries and become a beloved figure in a Sufi order—the only one who can communicate with the “holy man”. Yehia’s insecurities and are beautifully shown in this film, a powerful contender for the Youssef Chahine Award which is given to the Best Short Film at CIFF. Filmed in Cairo’s historic cemeteries, Shawky’s film will be screened in the legendary Ewart Hall at the old campus of the American University in Cairo, very close to the Cine Radio, one of the oldest cinemas in the country where dozens of Mahfouz’s films were screened.

Inside the Egyptian Opera House — which is 10 minutes walk from Tahrir Square, the birthplace of the 2011 Egyptian revolution where almost half a million people demanded Bread, Freedom and Social Justice — the festival is screening Cairo 30 (1966), adapted from the novel Cairo Modern. This masterpiece directed by the father of Egyptian realism, Salah Abu Seif, imagines a socialist solution to Egypt’s eternal problems: class struggle, societal decay, and corruption. It is the early 1930s after the death of influential nationalist leader Saad Zaghloul and the appointment of Ismail Sidqi as prime minister, which transformed the “liberal” era of Egyptian politics into a scene of factionalized parties competing to form a government. Ironically, in the same month that Cairo 30 is screening again in cinemas, Egypt has annulled the results of the first round of November parliamentary elections across seven governorates due to severe violations, including illegal campaigning.

Still From Cairo 30 (1966)

Another example of films that use politics to highlight their message is Houssam El-Din Mustafa’s The Quail and Autumn (1967), which explores the existential crisis of a man forced to leave political life after the 1952 revolution. Meanwhile the gem by Houssam El-Din Mustafa is The Beggar (1973), a compelling exploration of existential crisis and disillusionment, tradition and progress.

Almost 20 years after his death, Mahfouz’s legacy continues to be present on the Egyptian cultural scene. It is not controversy alone that makes his work — and its influence on artists and filmmakers — unique, but its ability to mirror societal disease, institutional anxieties, and individual aspirations through stories that still speak to the fragility and resilience of everyday Egyptian life.