Wuthering Heights

Wuthering Heights

VERDICT: Emerald Fennell’s take on Emily Brontë offers the sumptuous trash that has become the auteur’s trademark, but her departures from the original story fall flat.

Big-screen adaptations of Emily Brontë’s legendary novel Wuthering Heights have often left out the second half of the novel, in which subsequent generations must reckon with the past. Not to be outdone, Emerald Fennell’s sumptuous, heavy-breathing take on the book decides to dump a great deal of the book’s first half as well, but for no apparent reason.

Not that a story from 1847 can’t be open to some degree of revisionism and reinterpretation — the director claims her quotation marks around the title indicate that it’s not a slavish recreation — but any artist with the chutzpah to tinker with one of the most beloved novels in the English language had better come to the table with meaningful changes, or at least a bold new perspective. Fennell provides neither; there’s a lot more sex in this Wuthering Heights, but the characters are flatter, the story is duller, and by the film’s climax, any dramatic momentum has been swept away by the winds on the moors.

In Fennell’s version, young Catherine Earnshaw (Charlotte Mellington) is an only child, raised by companion Nelly (Vy Nguyen) and her drunken father (Martin Clunes, Doc Martin). One day, Mr. Earnshaw brings home a nameless urchin (Owen Cooper, Adolescence), whom Catherine dubs Heathcliff, after her dead brother. Cathy treats Heathcliff as a combination pet, servant, and sibling, but he demonstrates his adoration for her, taking the blame for her transgressions to spare her from her father’s violent beatings.

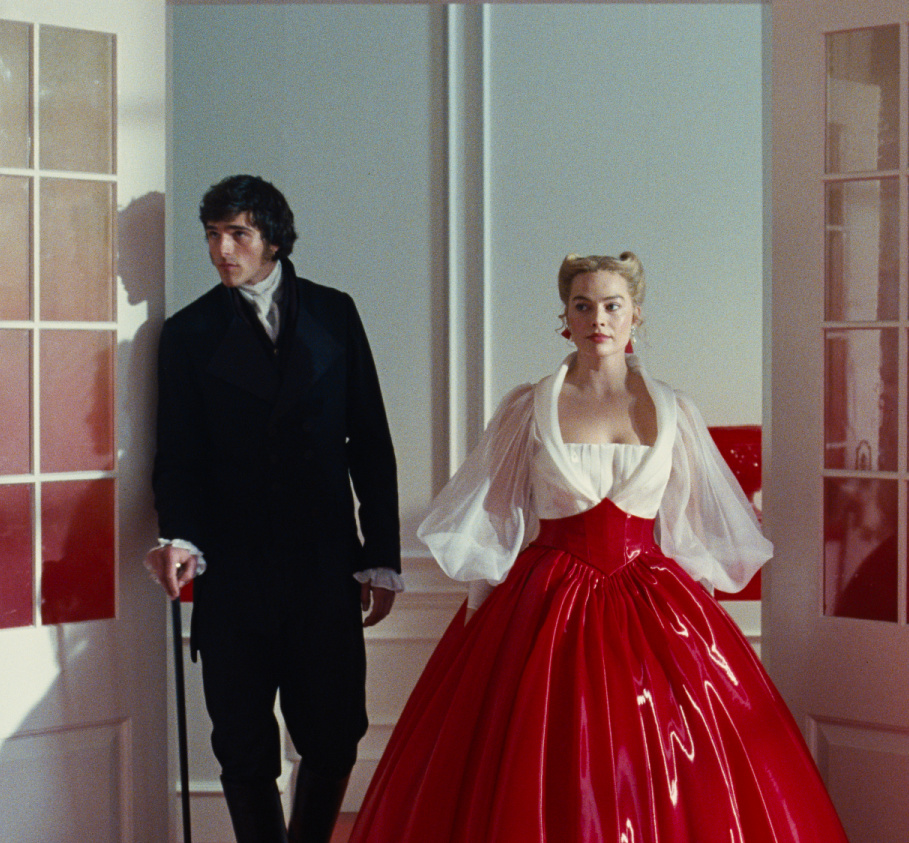

As young adults, Catherine (Margot Robbie) and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi) remain close, but when she is swept up into the world of their wealthy new neighbor Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif, Star Trek: Discovery), Catherine is torn between desire for Heathcliff and an equally strong need for wealth and stability. Nelly (Hong Chau), knowing that Heathcliff is listening, goads Catherine into confessing her doubts; Heathcliff departs, Catherine marries Edgar, and tragedy unfolds.

But not quite the same tragedy as Brontë detailed: when a wealthy Heathcliff returns, he’s not the same brutish sadist as in the book. It pleases him to be the new lord of Wuthering Heights, yes, but he doesn’t torture old Mr. Earnshaw the way he does Catherine’s brother in the book. Heathcliff marries Isabella (Alison Oliver, Saltburn) — now Edgar’s ward rather than his sister — but he informs the smitten young woman up front that he’s only doing it to torture Catherine, proceeding with a form of sexual domination only after Isabella agrees to it. (This is a very consent-conscious Heathcliff.)

If Fennell makes Heathcliff somewhat less nefarious, she does the opposite to Catherine, launching her into a passionate and clandestine love affair with Heathcliff without informing him that she is already pregnant with Edgar’s child. The tinkering with Brontë’s plot is sensational yet not substantive, as if Fennell were striking out in a bold new direction only to lose her way, and as the running time lumbers along, this Wuthering Heights deflates.

What holds the film aloft along the way are some incisive performances, with Mellington and Cooper ably setting the stage for Robbie and Elordi. (Elordi pulling off Elvis, Frankenstein’s monster, and now Heathcliff in a matter of years counts as an impressive trifecta for an up-and-coming movie star.) Fennell, to her credit, understands the passion and glamour that her leads provide, together and separately, and luxuriates in their tortured romance.

Visually, the film offers a banquet, from Linus Sandgren’s cinematography — which captures the Gothic ruins of Wuthering Heights and the wind-swept moors with equal brio — to the costumes by Jacqueline Durran; once Catherine marries into money, her ensembles grow more colorful and elaborate and ridiculous, capturing a perfect Brontë Barbie aesthetic. Production designer Suzie Davies (Conclave) gives Edgar’s palatial Thrushcross Grange a sheen of precision, a dollhouse writ large with its own dollhouse duplicate contained inside, one that provides a sort of commentary on the flesh-and-blood people acting out all around it.

Even with all these talented artists putting forth an impressive effort, Fennell continues her journey into lush absurdity. She loves parallel imagery — the welts on Heathcliff’s back and a corset digging into Catherine’s flesh, a white snail spreading its way across a window and Catherine’s wedding train billowing across the landscape — but these echoes ring hollow, calling attention to themselves without revealing deeper meaning. There’s plenty of technique but very little artistry in Fennell’s storytelling; in her efforts to deliver serious cinema, she may be turning into one of this generation’s leading purveyors of camp.

Director: Emerald Fennell

Screenwriter: Emerald Fennell, based on the novel by Emily Brontë

Cast: Margot Robbie. Jacob Elordi, Hong Chau, Shazad Latif, Alison Oliver, Martin Clunes, Ewan Mitchell

Producers: Emerald Fennell, Josey McNamara, Margot Robbie

Executive producers: Tom Ackerley, Sara Desmond

Director of photography: Linus Sandgren

Production design: Suzie Davies

Editing: Victoria Boydell

Music: Anthony Willis

Sound design: Nina Hartstone, Eilam Hoffman, supervising sound editors

Production companies: Warner Bros., MRC, Lie Still, LuckyChap

In English

136 minutes