- Home

- Reviews

- Festivals

- Featured Festivals

- Visions du Réel

- Stockfish 2024

- Berlinale 2024

- Rotterdam 2024

- Sundance 2024

- El Gouna 2023

- IDFA 2023

- Leipzig 2023

- San Sebastian 2023

- Oldenburg 2023

- VENICE 2023

- Toronto 2023

- Sarajevo 2023

- Locarno 2023

- Karlovy Vary 2023

- Annecy

- Cannes 2023

- Thessaloniki Docs 2023

- Berlin 2023

- Rotterdam 2023

- CAIRO 2022

- THESSALONIKI 2022

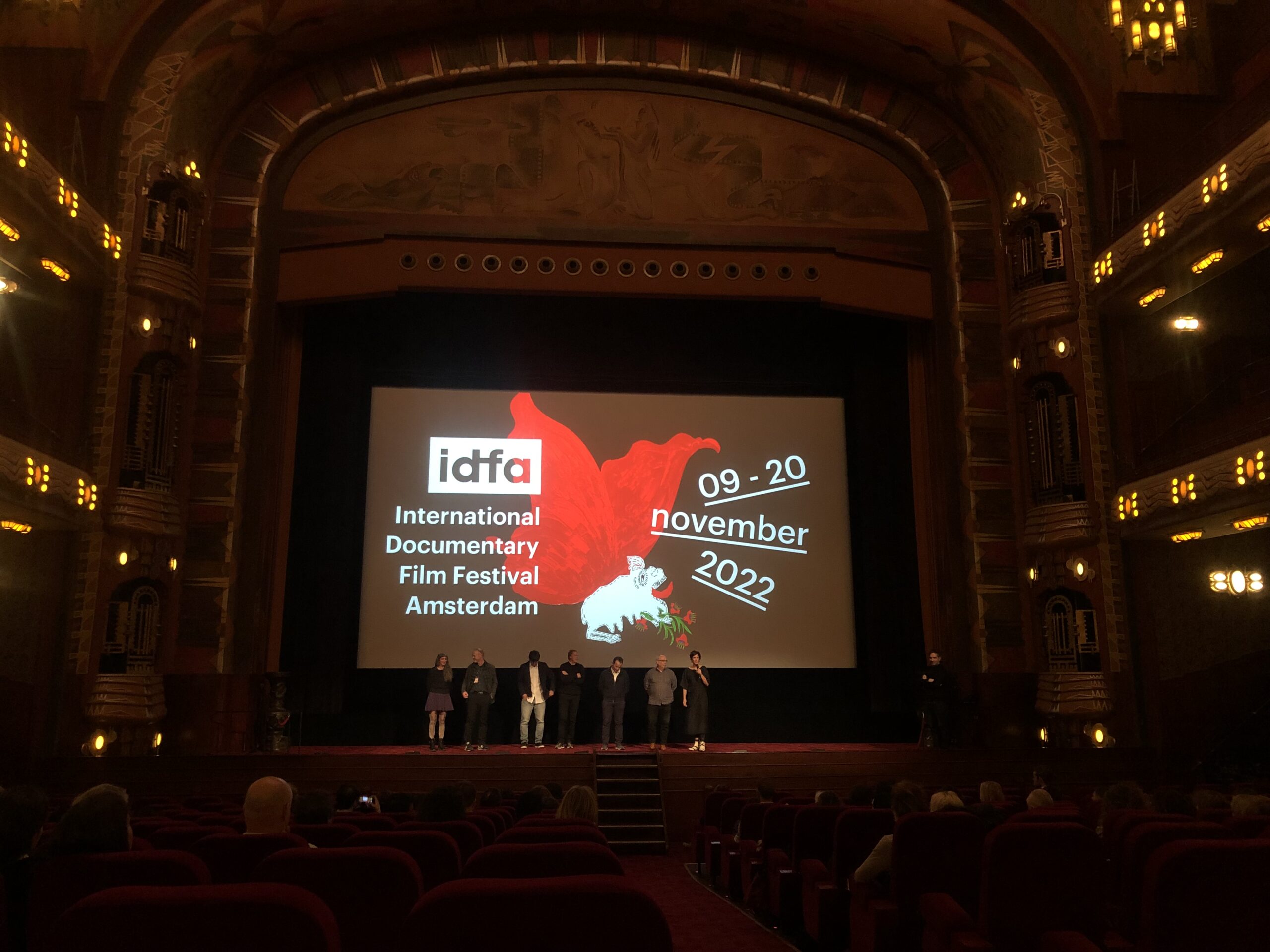

- IDFA 2022

- Morelia 2022

- Leipzig 2022

- Oldenburg

- San Sebastian

- Sarajevo

- Locarno

- Karlovy Vary

- Rotterdam

- Cairo

- Berlin

- CANNES 2022

- IDFA

- Tallinn

- Thessaloniki

- Morelia

- El Gouna

- London

- Featured Festivals

- Featured Festivals

- Verdict Shorts

- Screendollars

- Cine Verdict

- Interviews & Features

- Newsletters

- FestMarket Clips

- Locations

Select Page