Life after Siham

.

VERDICT: Like Youssef Chahine’s quadrilogy, which explored his and his family's defeats, shames, and victories, Namir Abdel Messeeh’s tenderhearted documentary 'Life after Siham' turns private mourning into a quiet, searching act of cinema.

Some people break down, stay silent, remember incidents or laugh nervously when a parent dies. Egyptian director Namir Abdel Messeeh did what he knew how to do best when his mother Siham passed away: he picked up a camera. Grief arrives first and takes center stage in his documentary Life after Siham, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and is now being screened both as a Cairo Special Screening and making its Dutch premiere at IDFA’s Best of Fests.

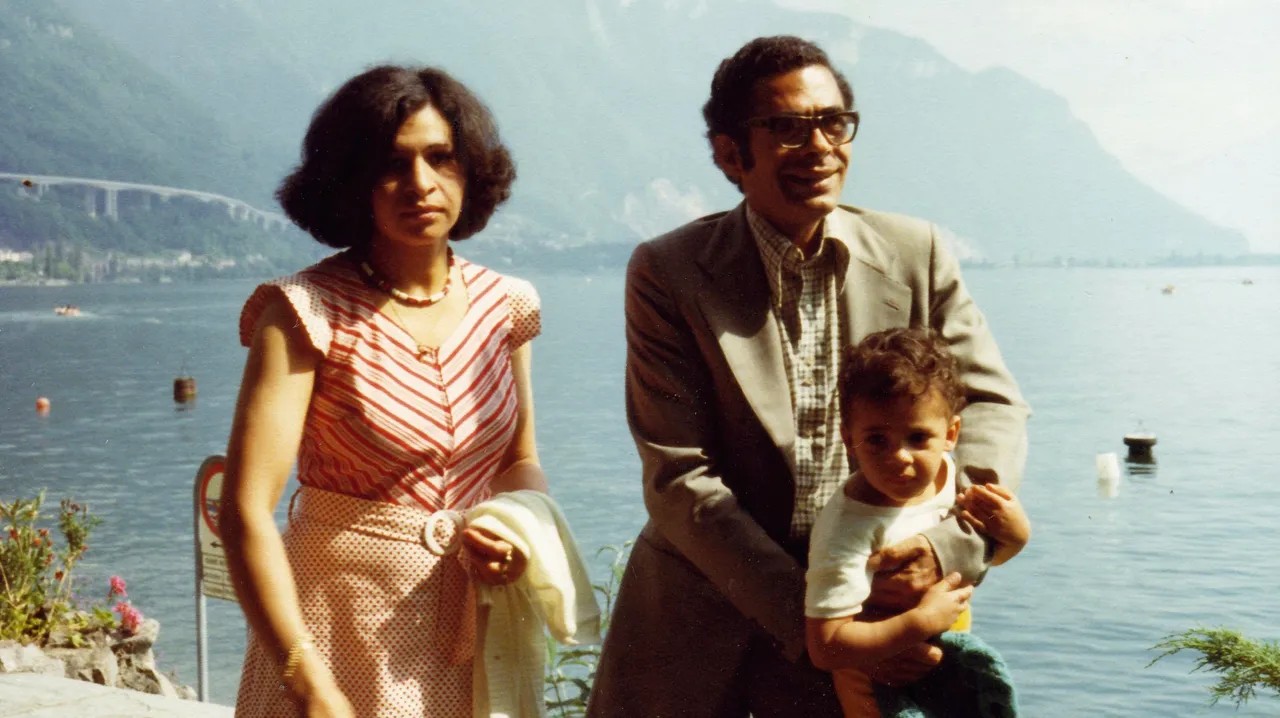

When Siham, the mother, is gone, her husband Waguih and their son Namir are left to make sense of what their lives will be “after” her. Her presence continues to fill their house, their memories, and the pictures that Namir has taken for years. Simply put, Life after Siham is the director’s attempt to keep a promise he made to his mother to make a “real film with actors” instead of casting his family members in it. He works with a collage structure, mixing old photographs, new footage of his father, present-day vérité footage, Super 8 reels, and excerpts from Youssef Chahine films.

The emotional core of the film is the triangle between Namir, his mother, and his father. The father is reserved and clearly protecting himself with silence and distance. Bit by bit, Abdel Messeeh is able to get him to reflect on the story of his marriage, which started as a romance in the 1960s in Egypt and turned into a marriage in exile in France in the 1970s.

Much of the film is built from the material Namir gathered in the months after his mother’s death. He starts by filming inside the family’s apartment in France, where his father, Waguih, now lives alone. The camera records the daily routines of a widower: silent breakfasts, the way he handles old photos or just sits in his chair thinking. These scenes form the emotional spine of the film, including ones where Namir pushes him gently into conversation, asking him about their early years in Cairo and how he met Siham. The grief of both men collides in the presence of the camera and becomes part of the documentary’s fabric.

Namir also travels to Egypt to film and understand the places and people that shaped his parents’ story. Starting with Cairo, he aims to trace the couple’s early life, their political activism, and the repression they were subjected to. Then he goes all the way to the south of Egypt (Upper Egypt) to film his aunt. Having directed The Virgin, the Copts and Me (2011), he is not a stranger to Copts living in Upper Egypt. As expected, the scenes there are looser, filled with warmth, honesty, some laughter, urban legends, and teasing — a freedom to speak in front of the camera that his father cannot do. There are topics like migration, separation, childhood, and Siham’s character, revealing parts of the family history that Waguih prefers not to discuss.

Throughout the film, the director uses old photographs and Super 8 reels to retell his parents’ story, brilliantly inserting scenes from Youssef Chahine’s The Return of the Prodigal Son and Dawn of a New Day, which he repurposes as “stand-ins” for moments in his parents’ life together. This choice is on target, practical, and poetic. It fills the gaps where no personal footage exists, especially moments of the parents’ youthful romance in Cairo, the tensions of exile, and the political pressure in the 1970s. It beautifully lets cinema act as filler for missing moments. In addition, it redefines documentary filmmaking as a medium that can borrow and sample existing films to express a past moment.

The hybrid territory which Namir creates by mixing different mediums allows him to get into the political context, which in many ways forced his family to emigrate from Egypt. His father was a leftist under the socialist-leaning president Nasser, but when the regime changed he paid a price under the capitalist-leaning Sadat. A Coptic Christian and a communist, Waguih found himself rejected for jobs and pushed out of academia. His exile in France is not presented here as a heroic choice but rather as a last resort to avoid imprisonment and further marginalization.

Living “after” Siham, the director is forced to conclude there is no clear “after.” His parents don’t simply vanish. Their existence passes into stories, pictures, and letters that they leave behind, and most importantly, they pass on their habits and bodies to their children and grandchildren. The filmmaker, like anyone grieving for a loved one, doubles back, contradicts himself, and lets memory remain unresolved.

Sound plays a subtle role in the documentary. The calm voice-over is often searching, hesitant, but never dictating. Songs drift through the film like Mohamed Abdel Wahab’s “Ya Musafir Wahdak” and Abdel Halim Hafez’s “Ana Lek ‘Ala Toul”, echoing gentle meanings about loyalty in love and longing for the beloved’s company.

Like many personal documentaries, the camerawork is modest, shot with handheld cameras with close framing, sometimes trembling, giving away how personal the material is, and showing that the filming is part of the story. Namir Abdel Messeeh does not pretend to be a neutral observer, as he often shows the retakes and the awkwardness between himself and his father, including the power dynamics and discomfort that come from being recorded.

Director, screenplay, producer: Namir Abdel Messeeh

Co-producer: Camille Laemlé

Cinematography: Nicolas Duchêne

Editors: Benoît Alavoine, Emmanuel Manzano

Sound: Roman Dymny, Julien Sicart, Thomas Robert

Sound design: Roman Dymny

Music: Clovis Schneider

Production companies: Oweda Films, Les Films d’Ici

World sales, screening copy: Split Screen

Venue: Cairo Film Festival (Special Screenings)

In French, Arabic

80 minutes