San Sebastian 2021: The Verdict

VERDICT:

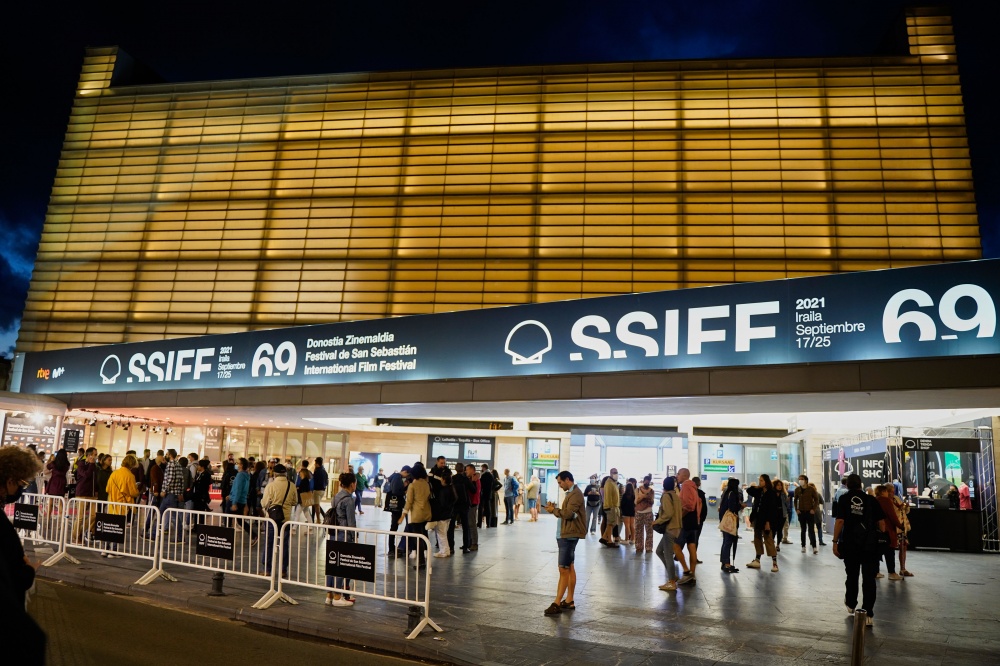

The crowds were back at the 69th San Sebastian International Film Festival (around 90% compared to 2019 levels), but not the carefree atmosphere of leisurely walks with friends, meetings in the crowded pintxos (snack) bars, and swims on La Concha beach, for which the Basque city on the Atlantic was justly beloved before the pandemic.

Festivals were clearly designed as places to exchange viewpoints, but getting back to normal is proving a slow process. Just like Venice, accreditations far outpaced available seating at the screenings (theaters were operating at 50% capacity), and the 7:00 a.m. ticketing system was even more Byzantine and punitive than the Lido’s. Why should it be necessary to show an e-ticket on your phone, when it’s already on your scanned badge? Forget meeting friends; welcome to the new (hopefully temporary) normal, an anxious and frequently solitary festival experience.

Known as Donostia Zinemaldia to the local Basque residents, the San Sebastian fest has always followed its own interesting path, incorporating local culture into a very large event full of sidebars and sub-sections. It is one of the world’s only festivals that translates subtitles into three languages (Spanish, Basque and English) at different screenings, and it has always been complicated. (This year, adding to the atmosphere of emergency, ten health commandments were read in all three languages before every film!)

It was up to the movies to make the restriction-laden trip to Spain worth it, and the choices of fest director José Luis Rebordinos and his programmers rarely disappointed. One area where the festival excelled was its successful integration of women directors into the competitive sections. The proof? Almost all the awards went to women – plus best screenplay to Terence Davies, whose moving comeback film Benediction explored the life and loves of poet Siegfried Sassoon and the devastating trauma he underwent fighting in the trenches of World War I.

A glance at the 17 feature films presented in the main Official Selection included seven by female filmmakers, and unlike some festivals where gender inclusion feels forced and uncomfortable, they were all worthy titles. It’s not difficult to find their common thread, since all seven films put women in the forefront; even Claire Simon’s curious but well-liked story about writer Marguerite Duras’s male partner in I Want to Talk about Duras is dominated by the grande dame. Iciar Bollain’s Maixabel portrays the real-life, strong-minded widow of a victim of Basque terrorism, and Ines Barrionuevo’s Camila Comes Out Tonight leaves no doubt that its self-possessed heroine, an Argentinian high school girl exploring her bisexuality, will triumph.

But creating the most buzz were two films that pushed beyond classic drama into psychological zones of the unconscious: Earwig, the first English-language feature by French director Lucile Hadzihalilovic, which won the Special Jury Prize awarded by Georgian filmmaker Dea Kulumbegashvili’s jury, and Romanian director Alina Grigore’s accomplished and absorbing first feature Blue Moon about a young woman struggling to liberate herself from her violent family, positively electrifying in its banality, which won the Golden Shell for best film.

Not to be forgotten was Tatiana Huezo’s much-talked-about and admired Prayers for the Stolen (Noche de Fuego), whose extraordinary female cast communicated the anguish of living side-by-side with the drug lords of San Salvador, Mexico; it won the laurels in the Latin Horizons section.