Dreaming & Dying

Hao jiu bu jian

VERDICT: Magical realism and Far East ghost stories inject a thrilling, if not always crystal clear, element into Nelson Yeo’s fishy tale of an overage and not completely human love triangle, ‘Dreaming & Dying’.

The winner of two major Locarno awards — the Golden Leopard in the Filmmakers of the Present section, as well as a Best First Feature nod to director Nelson Yeo – Dreaming & Dying is now embarked on a lively festival career, where this offbeat but straight-faced tale of a man, a woman and a merman should earn respect for the Singaporean Yeo and his sensuous, romantic, and at times humorous vision of love and loss over multiple reincarnations.

On the other hand, viewers are likely to react in different ways to the abrupt flights of fancy that interrupt the tired reunion of a husband and wife with a school chum they haven’t seen for years. The setting is a tropical resort where the trio seem to be the only guests – in fact, the only people seen in the film, apart from some background figures. Amid an overgrown id of untended vegetation, a sparkling azure swimming pool becomes the stage where the never-named husband and wife (Kelvin Ho and Doreen Toh) glare at each other as they try to revive some kind of meaningful relationship with the taciturn Heng (Peter Yu) — the only other person who has showed up for the class reunion. It emerges that the boorish husband (the “class monitor”) bullied Heng in school, while his wife had a youthful romance with him.

They are all pushing 60 but Heng has kept in enviable shape, as he demonstrates by effortlessly swimming laps in the pool. The film’s opening scenes have a vague air of menace hovering over them, with the couple’s suppressed anger seeming ready to burst into violence and lead to a crime, perhaps even a murder. But then the camera begins to plunge underwater and Yeo’s screenplay changes register.

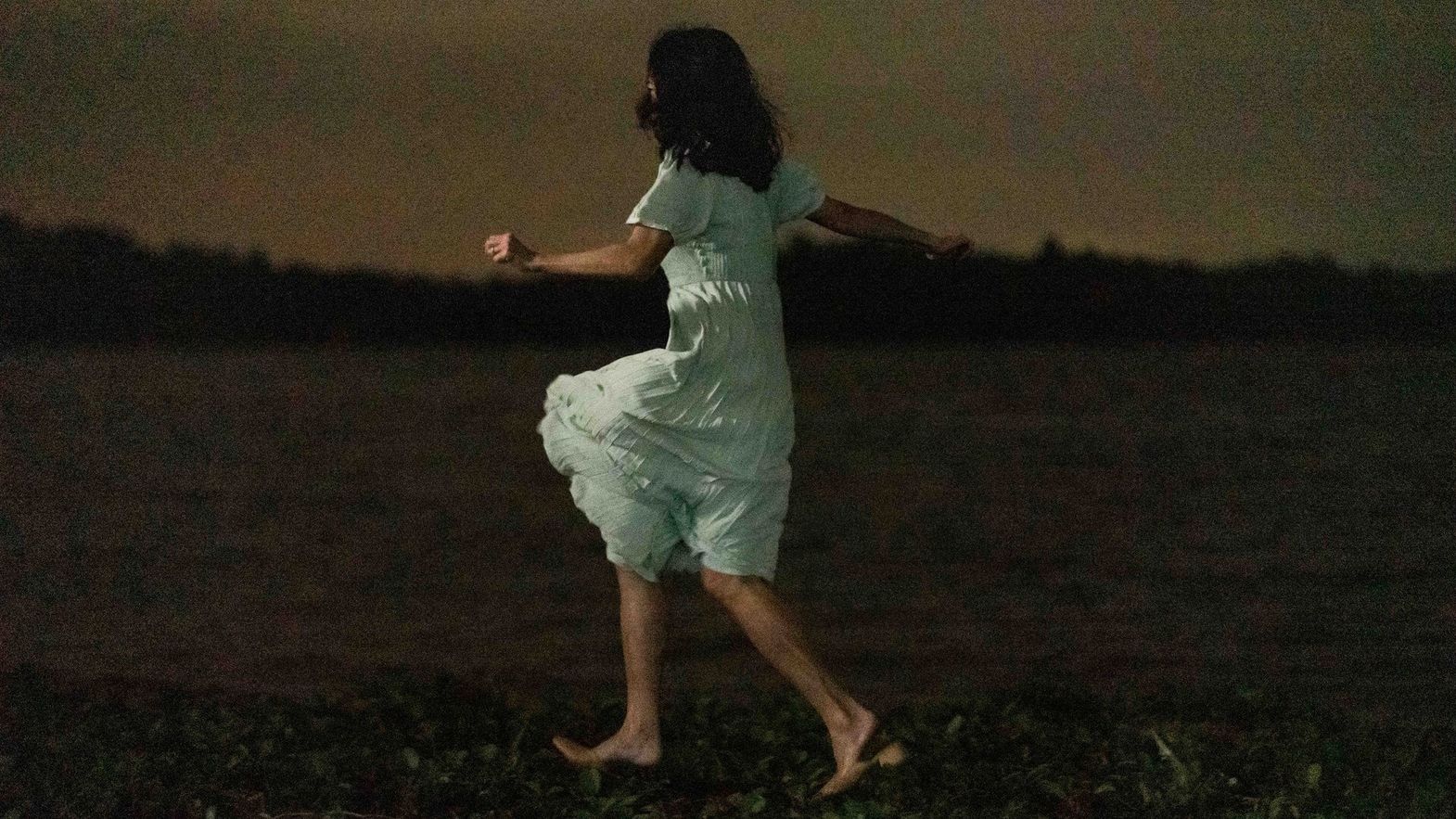

Up to this point the dialogue has been purposefully banal and redundant, not to say irritating, like the wife’s fantasies of seducing Heng with a few well-turned words. The turning point comes when she reappears in what is apparently an earlier time, dressed with the breezy, billowing femininity of a young woman, beside Heng with his long graying hair cut in a retro style. Interestingly, no attempt is made to rejuvenate their faces, suggesting this is some kind of a memory. In this long-ago tete-a-tete, delicately poised between the romantic and the ludicrous, Heng hesitantly reveals the true obstacle to their love: he has a long fish tail instead of legs.

Perhaps more than flashbacks, these windows on the supernatural – directly calling up major influences on Yeo like Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Filipino master Lav Diaz – fall into a category bridging dream and imagination, which are left fluid and up to the viewer to decide whether to go with the flow or feel disaffected by a frustrating lack of narrative progress. And the editing is leisurely, though admirable in not adding confusion to a difficult story.

The nonhuman drama is casually intercut with a pilgrimage the unhappy couple is making on the advice of a priest, apparently to release the husband’s bad karmas and improve his flagging health. The idea is to cart around a live fish in a Styrofoam box and release it into the sea, burning incense and reciting prayers along the way. Engaged in their common purpose, the couple does not seem quite so hostile to each other, and at one point the ailing husband awkwardly tells his wife he’s like to “start over”. Though the narrative path goes off on a lot of detours, with various accidents and disappearances and the fish almost dying, it does eventually lead to a surprise conclusion that, thanks to Doreen Toh’s expressiveness even in long shot, could be described as moving.

It seems clear that Yeo’s screenplay refers not just to contemporary Asian cinema but to the culture’s fables and folklore, from whence come talking fish and the unsettling background noise of a giant beast snoring. But just as you don’t need to have read the Brothers Grimm to get their scary vibes, so here the sense of supernatural danger is clear. It will be more of a stretch for some audiences to accept the film’s quirky tone, in-between real human feelings and farcical situations.

To his credit, Yeo stretches his budget remarkably well, making do with a simple cloth fish costume to turn the stylish Heng into an equally stylish sea creature. All three actors, who initially seem very nondescript, reveal depths of character, even Kelvin Ho’s exasperating husband who is always falling down. The tropical atmosphere blends easily into the characters’ mental landscape in D.P. Lincoln Yeo’s dreamy lensing that incorporates visions like brightly lit caves and an enchanting Buddhist temple floating on a still lake.

Director, screenplay: Nelson Yeo

Cast: Peter Yu, Doreen Toh, Kelvin Ho

Producers: Sophia Sim, Si En Tan

Coproducer: Yulia Evina Bhara

Cinematography: Lincoln Yeo

Editing: Armiliah Aripin

Art directors: Lou Shenna, Mark Chua, Li Shuen Lam

KCostume design: Lou Shenna, Megan Lim

Sound: Lijie Cheng

Production companies: Momo Film Co., KawanKawan Media, Widewall Pictures

World Sales: Lights On

Venue: El Gouna Film Festival (Out of competition)

In Chinese, English, Singlish

77 minutes