Lost Country

Lost Country

VERDICT: A teen comes of age as a troubled Serbia reckons with its direction in 'Lost Country', Vladimir Perisic’s sombre yet astute, politically-charged drama.

Vladimir Perisic’s Lost Country opens as a storm brews. The symbolism in his sombre but politically incandescent, urgent sophomore feature tends toward the heavy-handed, but the stakes are high in finding meaning, as it reflects on the 1996 local elections in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia as a dire crossroads for the nation’s future.

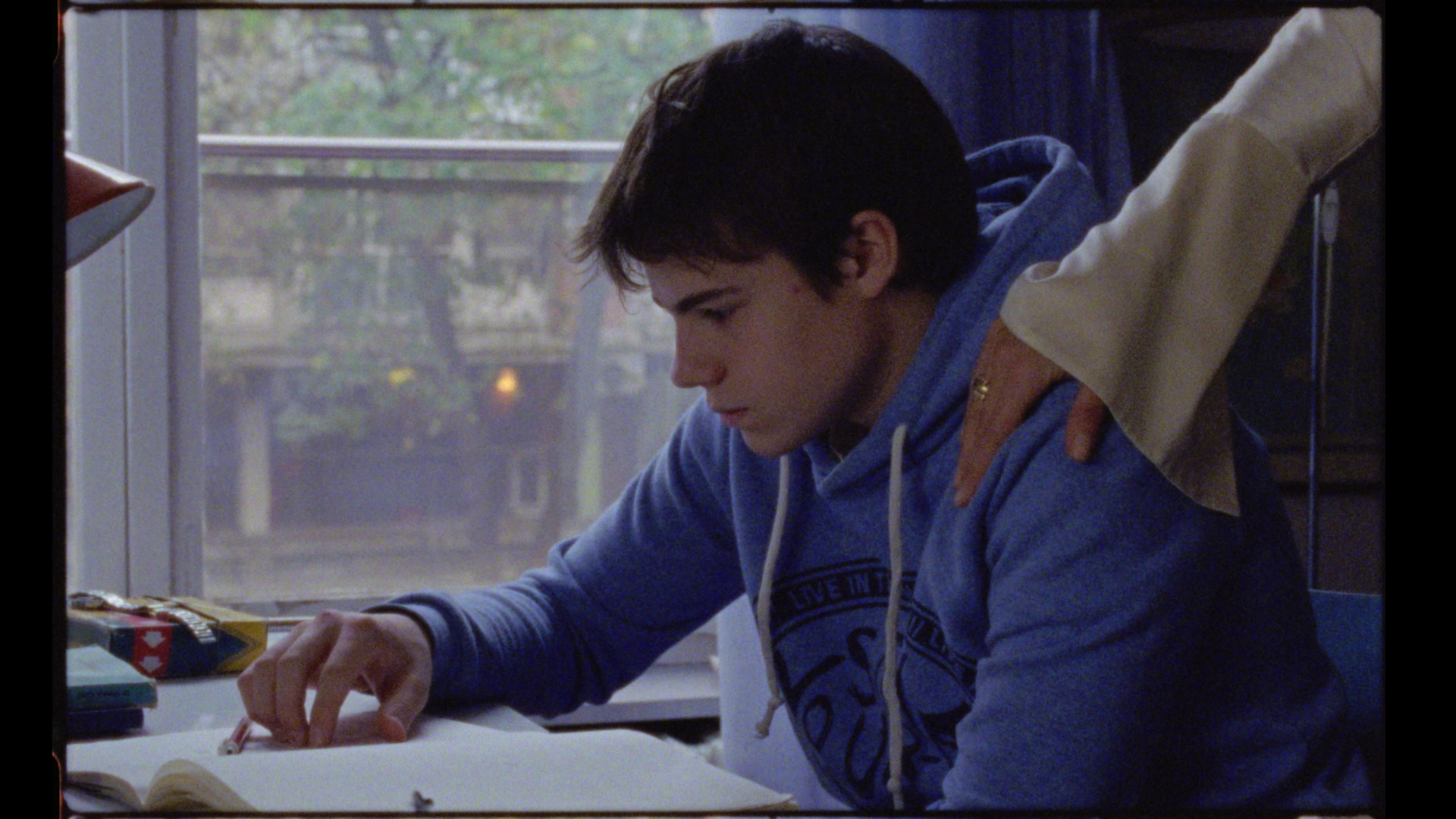

The threat of rain curtails an idyllic afternoon picking walnuts in the countryside for fifteen-year-old Stefan (Jovan Ginic), where his grandfather (Dusko Valentic) has been reminiscing nostalgically about his younger years as a water polo Olympian and anti-fascist partisan in Tito’s Yugoslavia. The darkening weather coincides with civil unrest on the streets of Belgrade. The party of authoritarian president Slobodan Milosevic faces defeat at the polls, and moves to cling onto power by falsifying results, with public relations help from Stefan’s mother (Jasna Duricic), their spokeswoman.

Following its Critics’ Week premiere at Cannes, Lost Country screens in the Feature Competition at Sarajevo Film Festival — a long-awaited return for Perisic since he won the Heart of Sarajevo Award for Best Film for his 2009 debut Ordinary People, which dealt with the dehumanising effects of the military on young men. It’s a coming-of-age drama that uses the inner struggle of Stefan, torn with conflicting loyalties towards his mother, a self-declared “patriot,” and his classmates, who are clamouring to join the resistance, to astutely reckon with Serbia’s path forward.

The split between those pursuing Milosevic’s nationalist, xenophobic agenda to create a Greater Serbia, and those advocating a turn to greater integration with Western institutions, as Yugoslavia fell apart, deeply resonates, amid the resurgent divisions of today’s Europe. Its gut-punching tragedy is that of generational trauma and schism, as Stefan’s emerging political consciousness comes with the realisation that his family is on the wrong side of history.

A strong identification with Communism has been instilled in Stefan’s family: his mother, after all, was not named Marklena (a contraction of Marx and Lenin) for nothing. Duricic, who recently brought her formidable acting chops to bear in Jasmila Zbanic’s emotionally devastating European Film Award winner on the Srebrenica genocide Quo Vadis, Aida? (2020), plays Marklena as an inscrutable woman operating on the blurred line where idealism has warped into corrupted opportunism. Elegantly put together, but inauthentic in her chronic avoidance of discussing the dirtier aspects of her campaign work, her demonstrative love for Stefan has an overbearing quality, and her commitment to excelling as a career woman has been co-opted for violent ends.

Marklena is out a lot at night, and her absences coincide with a growing teenage desire within Stefan to align himself more with his peers and interpret the world around him on their terms. But, as rallies gain momentum, the banging of pots and pans sound out fermenting discontent through the capital, and students are sent to jail for civil disobedience, tension with his friends increases. Out of shame, he tries to deny his mother’s role in the elections, but she is the public face of the Milosevic regime, deriding the protesters as mercenaries of foreign powers and NATO fifth columnists on television, and organising violent counter-rallies to quash the dissent. This is in stark contrast to one friend’s father, who is struggling with the psychological aftermath of serving as a fighter in Vukovar,. Despite having a political science degree, he cannot secure employment at a higher level than selling goods at a market, since he is not a party member.

Stefan’s new romantic interest Hana (Ana Simeunovic), who he keeps in the dark about his background, encourages him to become politically informed. They shoot pool together, and first love beckons — but in the tinderbox atmosphere, any prospect of carefree romance is pushed aside. She pushes him to consider solidarity with the ethnic Albanians in Kosovo that Milosevic has stirred up hatred for, and to join the crowds in Belgrade’s streets agitating for change.

In a clairvoyant vision, which adds to the sense of foreboding unease, Hana foresees a massacre of Albanians.

Sight is a pervasive theme (in another instance of on-the-nose symbolism, Stefan is diagnosed with a degenerative eye condition). Serbia’s future depends, after all, on the clear-eyed assessment of unfolding events and ideological ramifications. Mired in an inner conflict he finds it hard to articulate, with a family association that marks him as an outcast in a changing world, Stefan struggles to process and carry the weight of history. Alienated from family and rejected by friends, he is framed cut off and isolated from others. In between an idealised past and a future that doesn’t welcome him, his fate hangs desolately in the balance.

Director: Vladimir Perisic

Screenwriters: Vladimir Perisic, Alice Winocour

Cast: Jovan Ginic, Jasna Duricic, Dusko Valentic, Ana Simeunovic, Boris Isakovic, Pavle Cemerikic, Marija Skaricic, Helena Buljan

Producers: Janja Kralj, Nadia Turincev, Omar El Kadi, Vladimir Perisic

Cinematography: Sarah Blum, Louise Botkay-Courcier

Editors: Martial Salomon, Jelena Maksimovic

Music: Alen Sinkauz, Nenad Sinkauz

Production Design: Daniela Dimitrovska

Production companies: KinoElektron (France), Easy Riders Films (France), Trilema (Serbia), Red Lion (Luxembourg), Kinorama (Croatia)

Sales: Memento International

Venue: Sarajevo Film Festival (Feature competition)

In Serbian

98 minutes