Safe Place

Sigurno mjesto

VERDICT: Raw, authentic emotion and inventive lyricism combine in Juraj Lerotic’s sensitive, devastating reckoning with an acute mental health crisis in the family.

A young man navigating the shocking, confounding experience of his brother’s acute mental health crisis and suicide is the premise of Croatian director Juraj Lerotic’s sensitive, beautifully rendered and emotionally devastating debut feature Safe Place. The film’s ample merits were recognised upon its world premiere in Locarno, where it was awarded Best First Feature, with Lerotic named Best Emerging Director and Goran Markovic picking up a Best Actor gong, before screening shortly after at Sarajevo Film Festival. While its elegantly lensed, arthouse sensibilities and real-world psychological heft assure it wide festival play ahead, its close basis in Lerotic’s own personal experience, a genesis that is revealed early on with a daring, inventive divergence into lyrical, meta territory, mean it has the potential to contribute significantly to ongoing conversations about the shortcomings of mental health services in handling patients with critical needs.

Safe Place opens with Bruno (played by Lerotic himself) breaking down the door of the Zagreb apartment of his brother Damir (Markovic), who has just undertaken a very serious suicide attempt, and is losing a lot of blood. As ambulances arrive on the scene, we are immersed in the panicked confusion and desperate need to somehow avert catastrophe that grips Bruno for the duration of the film — a hellish predicament shared by the men’s mother (Snježana Sinovcic Šiškov) as soon as she is informed of the emergency. At the hospital, Damir is shunted between a flurry of professionals, and his physical condition is soon stabilised, but it is clear from the severity of his attempt and his dazed condition that he is far from out of the woods in terms of further potential self-harm. It is not known what mental health condition Damir, who has no history of suicidal ideation, has, and he is committed to a psychiatric institution for diagnosis (paranoid delusions are one of his symptoms, and Damir himself says the doctors suspect schizophrenia.)

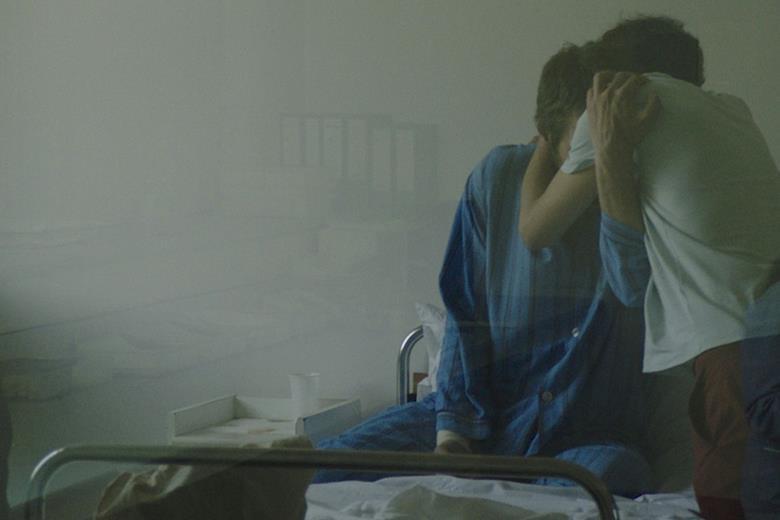

Markovic, his bearlike figure inert on hospital beds or seeking repose from company, convinces with a quiet and haunted, impenetrable look. Unable to connect rationally with the family worry and chaos around, he seems cloaked in solitude, his motivations unclear and his intentions unpredictable. He soon arrives back at his brother’s, having escaped the ward, and telling of cruel comments from psychiatric staff he distrusts. How much of this mistreatment is delusion and how much is real is impossible for his relatives to determine, though the patronising and dismissive treatment of his mother by a doctor upon her attempt to find out what medication he is on is enough to plant seeds of doubt in the family’s minds that his time in the institution may do more harm than good. And this is the real tragedy of the film: erratic and impulsively driven to injure himself, Damir is more of a handful than the family, adrift as to what he needs, can handle on their own. But, from distracted police who seem oblivious to the urgency of the situation, to mental health workers suspiciously devoid of empathy, it seems that support, and the safe place required, are elusive.

On one level, Safe Place adheres to a tight, suspenseful timeline over one frantic day, as the family, reluctant to return Damir to the institution against his will, break the law and drive with him to Split, their hometown, where to their anguish he will attempt suicide again. But time is elided at several points, making it clear that Damir has in fact died, and Bruno is making the film as a way to connect with the memory of his lost sibling, and come to terms with not having been able to save him. The disorienting nature of this revelation authentically replicates the jarring and fragmenting experience of trauma, and effects a dreamlike lyricism that echoes the human imagination under grief, as those left behind wish to see the deceased person again. The considered framing of cinematographer Marko Brdar, who presents the green hues and shining surfaces of the hospital as a world both beguiling and alien, helps to elevate the film with a feel of poetry, even as the relentless onslaught of tense emotion (both Bruno and his mother also need pills just to calm down) immerses us in the sickening roller-coaster of the family’s dread.

Director, screenplay: Juraj Lerotic

Cast: Snjezana Sinovcic Siskov, Goran Markovic, Juraj Lerotic

Cinematography: Marko Brdar

Editing: Marko Ferkovic

Set designer: Jana Plecas

Production company: Pipser (Croatia)

World sales: Pipser

Venue: Sarajevo Film Festival (Competition)

In Croatian

102 minutes